Periodontal diseases, which affect the supporting structures of the teeth, are a significant oral health concern worldwide, with the most severe form having an estimated prevalence of 7–11% and the mildest form almost 50%, making it the sixth-most prevalent disease worldwide (1,2). Although caries-related diseases often garner more attention among the professionals, recognizing and treating periodontal diseases are fundamental to good dental care. In this post, we will explore the coverage of periodontal status in Nordic countries and discuss the potential advantages of having high coverage.

Coverage of periodontal status varies among Nordic countries, with Sweden being the only one with a long history of national-level quality registers, that is, status coverage is available. Meanwhile, Finland and Norway are both introducing national registers that should be ready in the coming years, but Denmark has no quality register for oral health yet.

In Sweden, the Swedish Quality Registry for caries and periodontal diseases (SkaPa) offers wide coverage, and it includes public service provider data. Further, the SkaPa’s national average coverage of periodontal status from 2020–2022 was between 35–50%, depending on the age group. As such, variations among service providers are substantial, ranging from no records to full reporting (3).

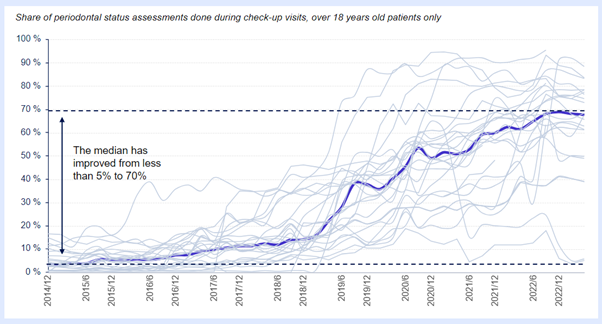

In Finland, the Nordic Healthcare Group (NHG) measures the coverage of periodontal status and the allocation of periodontal treatment across 30 Finnish public service providers responsible for a population of 4 million. In this context, the exact definition of periodontal status used by the NHG is a record of gingival pocketing or bleeding on at least one surface, which is thus far the best way to check periodontal status. However, when the NHG introduced its quality and outcome dashboard in 2015, only 5% of examined adult patients had a periodontal status, making it impossible to provide proper treatment and follow-up. Fortunately, by 2022, coverage of periodontal status reached 70% among examined patients (Fig. 1).

Finnish public service providers have different targets for periodontal status. For instance, based on Finnish national research (4), 64% of surveyed adults aged 30 years and over showed findings of periodontal disease. Further, in our experience, some Finnish organizations target about 60% coverage of periodontal status from patient examinations, while the others target 100% coverage, meaning technical marking is also applied to healthy patients.

Other methods of facilitating better periodontal health include dental care professionals specifically. Not long ago, diseases were deemed less critical than they are today. As such, the dental profession has been expanding from recording only traditional caries to including periodontitis. Ensuring diagnosis and treatment of Nordic patients with periodontal diseases according to the best practices requires much education and many incentives. In effect, in Finland, dental hygienists play a crucial role in supporting dentists with the necessary prevention and dental treatment. That said, the use of dental hygienists overall varies greatly among Nordic countries, a factor reflected in the differences in periodontal treatment.

Periodontal status itself does not improve anyone’s health, but recognizing this status is the only way to inquire about whether a patient’s treatment is progressing. It is also crucial to give patients all necessary information about the disease. On average, many Finnish organizations have reached the targets for periodontal status coverage, but the variations in results between dental clinics and individual dentists can be high, so the focus has now shifted toward more individual feedback.

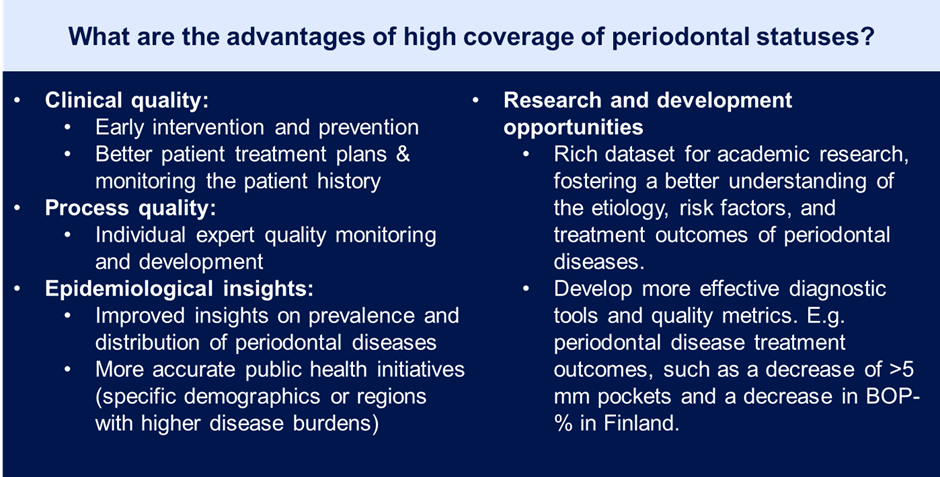

The next focus is ensuring patients with periodontal diseases receive the necessary treatment and confirming achievement of the treatment results. Having a structural periodontal status in the patient information system enables follow-up on population health and efficient treatments. In the figure 2 we have identified some advantages that high coverage of periodontal status enables. Some service providers are also taking steps toward integrated health services by identifying patients with type 2 diabetes and prioritizing periodontal treatment when necessary.

Discover More: Get your free guide on why and how dentistry is evolving. Our whitepaper, ‘Dentistry Needs to Change – Why and How?’ gives you insights into the changing world of oral care. Download it here.

- Eke, P. I., Dye, B. A., Wei, L., Slade, G. D., Thornton‐Evans, G. O., Borgnakke, W. S., … & Genco, R. J. (2015). Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. Journal of Periodontology, 86(5), 611–622.

- Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJL, & Marcenes W. (2014). Global Burden of Severe Periodontitis in 1990-2010: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression. Journal of Dental Research, 93(11), 1045–1053. doi:10.1177/0022034514552491

- Odontologisk Bokslut. (2022). SkaPa. https://www.skapareg.se/odontologisk-bokslut-2022

- Vehkalahti, M., & Knuuttila, M. (2004). Suun omahoito. julkaisussa L. Suominen-Taipale, A. Nordblad, M. Vehkalahti, & A. Aromaa (Eds.), Suomalaisten aikuisten suunterveys: Terveys 2000-tutkimus. Kansanterveyslaitoksen tutkimuksia B, Nro 16, Kansanterveyslaitos.